For the last two decades there has been growing interest in the arts within the protestant church. The voices of artists who are Christians from a Protestant tradition have been present in the 20th century through such persons as Hans Rookmaaker, Francis Schaeffer, Nicholas Woltersdorf, and the like.[1] But it has only been in the last 20 years that those voices have become more apparent. In fact the increased interest in the arts by the Church has gotten to the point where the questions are progressing from “What is art?” and “Is it important?” to “Who are artists?”[2]

This is significant, especially from a tradition that includes the “iconoclasts” in its history. Nevertheless, if this is a movement that is to have any sustainability, then more work has to be done in the area of theology in regards to aesthetics, beauty, and art. There is still a fear of representationalism within the Protestant tradition, and that fear is not unwarranted. But I believe it should not immobilize the Church, but challenge it to approach aesthetics, beauty, and art with a vigilant confidence.

What I want to do here is explore recent history of the art world in general and their recent “rediscovery” of beauty. I will try to define beauty (as much as it can be defined) and the related theological implications. And finally, I will show how the art of Makoto Fujimura is a tangible example of the crossroads of beauty and theology (probably one of the best examples today).

There are two things to keep in mind while reading this paper. First, as I have done my research on this topic I’ve realized how broad and deep it can and should go. This both excites and perplexes me, especially the number of resources I uncovered. I realize that the rest of my life will be filled with the exploration of such resources as I pursue beauty. This essay is NOT an exhaustive treatise—far from it—but one I hope to continue to add to and adjust for the rest of my life.

Second, I am biased—as I believe all people are. Each one of us looks at the world from a particular perspective, influenced by a myriad of ideas, experiences, and worldviews. My particular bias is Judeo-Christian. I am highly guided by the life, words, and works, of Jesus of Nazareth—the Christ. I believe his life, death, and resurrection have immediate consequences to all parts of life—most especially, as I hope to show, the place of beauty.

In the latter part of the last century the art world began to recognize a discernable amount of malnutrition in its philosophical “bones”. Gordon Fuglie recounts a moment—in the late 1980s, at an art conference of prominent dealers, artists, and critics—where an attendee asked respected art critic, Dave Hickey, what he thought would be the big issue of the next decade—the 1990’s—for the art world. Fuglie recounted, “For some reason still unknown to him (Dave Hickey), he snapped to attention and heard himself say, ‘The issue of the Nineties will be beauty.’ ”[3] This was quite an intriguing statement to make considering the assumed objective of art is to express and visualize the beautiful. Apparently, Hickey was stating the need for something that appeared to have been absent from the art world’s diet for a century.

Arthur Danto, in his book “The Abuse of Beauty” summarized it this way:

The philosophical conception of aesthetics was almost entirely dominated by the idea of beauty, and this was particularly the case in the eighteenth century – the great age of aesthetics – when apart from the sublime, the beautiful was the only aesthetic quality actively considered by artists and thinkers. And yet beauty had almost entirely disappeared from artistic reality in the twentieth century, as if attractiveness was somehow a stigma, with its crass commercial implications…“Beautiful!” itself just became an expression of generalized approbation, with as little descriptive content as a whistle someone might emit in the presence of something that especially wowed them.[4]

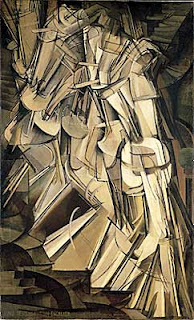

69th Regiment Armory Building in Manhattan

This “disappearance” of beauty was also evident in academia. In her book On Beauty and Being Just, Elaine Scarry wrote of “The banishing of beauty from the humanities…for distracting from social justice…”[5] Her book was based on lectures she gave in 1998 at Yale University. She was attempting to make the case that beauty was in fact essential for the carrying out of justice, a case she felt she needed to make in order to teach aesthetics at Harvard where she was a professor. Danto exposed this “banishment of beauty” more clearly when he wrote:

So it was no great loss to the discourse of…art (or beauty) when early Logical Positivists came to think of beauty as bereft of cognitive meaning altogether. To speak of something as beautiful, on their view, is not to describe it, but to express one’s overall admiration. And this could be done by just saying “Wow” – or rolling one’s eyes and pointing to it. Beyond what was dismissed as its “emotive meaning”, the idea of beauty appeared to be cognitively void – and that in part accounted for the vacuity of aesthetics as a discipline, which had banked so heavily on beauty as its central concept.(my note)[6]

Entrance to the Exhibition 1913, New York City

The Logical Positivists started their rise to influence in Europe right after World War I—especially during the 1920’s and 30’s. Interestingly, some art critics and historians cite the Armory show of 1913 as the onset of new perspectives on beauty in the 20th century—a viewpoint that has been, and is still being found lacking.

to be continued…

[2] Barabara Nicolosi, President of the screen writing program Act 1. said this in a speech at an arts conference in 2008. It is recorded in the book: Taylor, David O. For the Beauty of the Church: Casting a Vision for the Arts, Grand Rapids, MI, 2010, p105.

[3] Fuglie, Gordon. edit Prescott, Theodore L. A Broken Beauty. Grand Rapids, MI. 2005 p68. see also Hickey, David. The Invisible Dragon: Essays on Beauty. Chicago, IL. 2009.